“It’s spooky. What’s it like at night? Do you hear anything?”

It’s probably not the ideal way a recently renovated boutique hotel wants to be talked about.

But how many hotels are housed in a structure so confronting? It has even become the inspiration for a zombie laden computer game.

You don’t open a hotel in a giant abandoned asylum if you don’t want to embrace its eye opening – and somewhat surprising – history.

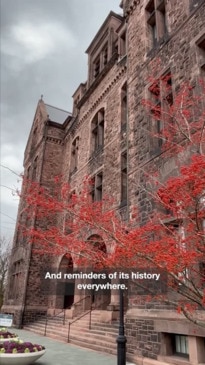

Welcome to the Richardson Hotel, perhaps the most unique place to stay in Buffalo, the second city of New York State, close to Niagara Falls.

Its corridors – bathed in soft light and lush furnishings and echoing to the noise of chinking glasses from the bar below – are a far cry from the asylum of old.

But the hotel only takes up a small proportion of what used to be the Buffalo State Insane Asylum. Much of it remains, just a few steps away: dark and almost forgotten.

Beyond the wings that are now filled with cheery visitors dining on scallop risotto and pasta Pomodoro and gulping down glasses of pinot grigio are abandoned corridors with fading paintings on the walls and wheelchairs covered in several decade’s worth of dust.

News.com.au took a look inside the building’s snazzy hotel side – and the asylum side that’s frozen in time.

‘Decline was quick’

“I have a word for this place: austere,” says Patrick F Ryan, the historian at the Richardson-Olmsted campus, where the monolithic structure now stands.

“By the time you get to the 20th century, the whole asylum movement as an ideal is shifting and combined with a large building that’s falling apart and overcrowding, the decline of this place was relatively quick.

“In 1974, the last patients came out. They just left everything behind, locked it up and said good luck”.

The asylum’s gradual metamorphosis – from still abandonment to buzzy hotel hotspot – is a mirror of Buffalo itself.

This is a city that lost much of its industry and half its population after it fell on hard times.

But it too is changing – breweries and markets are taking over once silent warehouses; bakeries serving fat, flaky croissants are opening up on street corners and an art gallery worthy of a major capital has just opened after a $300 million extension.

The Richardson Hotel sits within what were the central wings of the asylum.

To gain access to the older, non-refurbished parts, involves scurrying through a fenced off side entrance.

Rusting wheelchairs

It’s the cold that hits you first – the thick walls banish any winter warmth from outside.

Paint, a different colour for each wing, peels off the walls. Wooden doors, long fallen off their hinges, are propped up hoping one day to be reattached.

Next to a fireplace sits an eerie rusting wheelchair, not used since the 1970s.

Seeing it brings it into focus what a challenge it was to turn a mental institution into a boutique hotel, especially one that was built in 1872.

The basic design of the asylum and hotel are the same with wide corridors between the rooms.

In the asylum side, floorboards are scratched or some places missing completely. In the hotel there is plush carpet.

Walk down the corridors of the hotel and you’ll see what look like large wooden linen closets.

They’re actually the en suite bathrooms, punched out the walls, to subtly create more space.

They were essential because patient rooms in the asylum were only 2.7m wide by 3.3m long.

“The idea was this was they were just for bunking,” said Mr Ryan.

“(The rest of the time) you’d be out on the farm, doing exercise (in the gardens) or mingling.”

Secret inside

Inside the State Asylum was something of a secret world. This was not the mental institution conjured up in many a Hollywood picture. Strait jackets for instance, that trope of mental institutions, were rarely used here.

Rather, it had qualities of the finest hotels of the time.

“It served as the pinnacle of mental health treatment in the 19th century. They tried to give people as much humanity as possible,” said Mr Ryan.

Upon its opening in 1880, there were rooms where people could play board games or billiards. There were was even a ballroom and swish dining facilities.

“There were white tablecloths, candelabras and they imported china from England for the patients to use. It was very upscale,” said Mr Ryan.

A jazz saxophonist would come to the asylum to teach music therapy.

The style of care was the brainchild of devout Quaker Thomas Kirkbride who advocated outdoor recreation and the benefits of natural light.

He worked with architect Henry Hobson Richardson and the landscape team of Frederick Law Olmsted who designed New York’s Central Park.

Patients would come in usually due to suffering from “melancholy” or “mania” as mental health was characterised then. A proportion of that was syphilis.

It wasn’t a long term facility. As patients recovered they would be progressively moved from the outer to inner wings, literally and figuratively closer to the exit.

Influence on Australia

Mr Kirkbride’s model of mental health care made its way to Australia.

The Callan Park Hospital for the Insane, in Rozelle in Sydney’s inner west, opened in 1885, and was based on Buffalo with decorative elements and courtyards, designed to calm the mind.

‘Castles for crazy people;

The aims for Buffalo were high. But it began to suffer.

“The state moved far people than it could handle into the State Asylum,” said Mr Ryan. “You have a place built for 650 patients with close to 4000.”

Politics then intervened.

“One governor is actually quoted as saying ‘why are we building castles for crazy people?’”

Funding began to dry up, then two world wars saw staff numbers hugely reduced.

A model facility was now overcrowded, understaffed and in disrepair. Eventually it was replaced.

Too expensive to tear down, it was left to rot.

“They didn’t even leave the heating on. Forty years of Buffalo winters have ripped through the broken windows of this place,” said Mr Ryan.

Inspiration of horror computer game

It had gone from the ideal institution to, quite literally, the stuff of nightmares.

In the 2013 survival horror computer game Outlast, it served as the inspiration for a psychiatric hospital full of homicidal patients.

The game’s “Mount Massive Asylum” is clearly the Buffalo Asylum.

“Anything that’s falling apart and vacant, takes on a creepy air,” said Mr Ryan.

“You see these giant complexes where your grandmother might have said ‘oh that’s where the crazy people lived,’, then there’s the movies, games and all of these places just get this negative connotation. When in reality they were built to help people

“It’s the continued misunderstanding of mental health.”

The current custodians have steered clear of any tacky “ghost tours” or the like. Mr Ryan said it sullies the history of the building and the memories of those who passed through it.

The asylum’s slow ossification seemed a reflection of Buffalo itself which, at the end of the 20th century, was full of similar grand but decaying buildings emptied by the pains of post industrialisation.

But, slowly, as the new century dawned, concerted efforts were made to preserve Buffalo’s immense built environment.

It wasn’t just the Richardson-Olmsted Campus. Just a few minutes’ walk away is the Buffalo AKG Museum. A grand art gallery, impressive for a city the size of Buffalo, it’s the sixth oldest public art museum in the US.

It reopened last year after a massive $300 million refurbishment and expansion.

Van Goghs, Gaugins and Picassos can be found here along with a rich delve into more contemporary art.

Across the road, the Burchfield Penney Arts Centre showcases the work of watercolour painter Charles Burchfield as well as notable artists from the Niagara and western New York region.

Jump in a cab to inner Buffalo – to the tree lined streets of Allentown and Elmwood – and you can barely move for coffee shops, bars and restaurants.

In The Richardson’s cosy rooms it’s hard to think that one wing along, this historic building still lies desolate and deserted.

But not for long. The hope is the remainder will be transformed into apartments and a museum. It will be bustling once more.

“The plan for the campus is to give it back to the community and take some of the stigma of these buildings away,” said Mr Ryan.

More Coverage

Maybe, one day, the vivid imagination of the city’s taxi drivers will be less excited about this arresting piece of history.

And, maybe it’s just the thick walls and soft duvets – but no, nothing untoward was heard during the night.

The reporter travelled with the assistance of Visit Buffalo Niagara

Adblock test (Why?)

https://news.google.com/rss/articles/CBMitAFodHRwczovL3d3dy5uZXdzLmNvbS5hdS90cmF2ZWwvZGVzdGluYXRpb25zL25vcnRoLWFtZXJpY2EvbmV3LXlvcmsvc2VjcmV0cy1vZi1naWFudC1hYmFuZG9uZWQtaW5zYW5lLWFzeWx1bS10dXJuZWQtaW50by1hLWJvdXRpcXVlLWhvdGVsL25ld3Mtc3RvcnkvYjRjYjJhOTkyNTk0OWE0M2UyOWQ4ZGUzMDM5ZDdhOTHSAQA?oc=5

2024-03-30 08:49:49Z

CBMitAFodHRwczovL3d3dy5uZXdzLmNvbS5hdS90cmF2ZWwvZGVzdGluYXRpb25zL25vcnRoLWFtZXJpY2EvbmV3LXlvcmsvc2VjcmV0cy1vZi1naWFudC1hYmFuZG9uZWQtaW5zYW5lLWFzeWx1bS10dXJuZWQtaW50by1hLWJvdXRpcXVlLWhvdGVsL25ld3Mtc3RvcnkvYjRjYjJhOTkyNTk0OWE0M2UyOWQ4ZGUzMDM5ZDdhOTHSAQA