Spoilers follow for “All My Life, My Heart Has Yearned for a Thing I Cannot Name,” the season-two finale of Euphoria.

Amid all the chaos of the Euphoria universe in season two — the heroin, the sexualized fever dreams, the difficulty in getting body glitter out of one’s laundry — the finale episode “All My Life, My Heart Has Yearned for a Thing I Cannot Name” actually wrapped up a fair amount of arcs and loose ends. Rue quits doing drugs as easily as Miranda kicked alcoholism in And Just Like That…, telling us through her customary voiceover narration that she stayed clean through the end of the school year. Cassie and Maddy reach a kind of detente after fighting over Nate, and even hint at a John Tucker Must Die team-up with Maddy’s “This is just the beginning” line. Nate turns his father Cal into the police for “everything,” leading to the elder Jacobs’ arrest at one of his many under-construction properties. But any kind of closure for our favorite sensitive bad boy, Fezco? That remains a mystery, as does Sam Levinson’s long-term plan for this character.

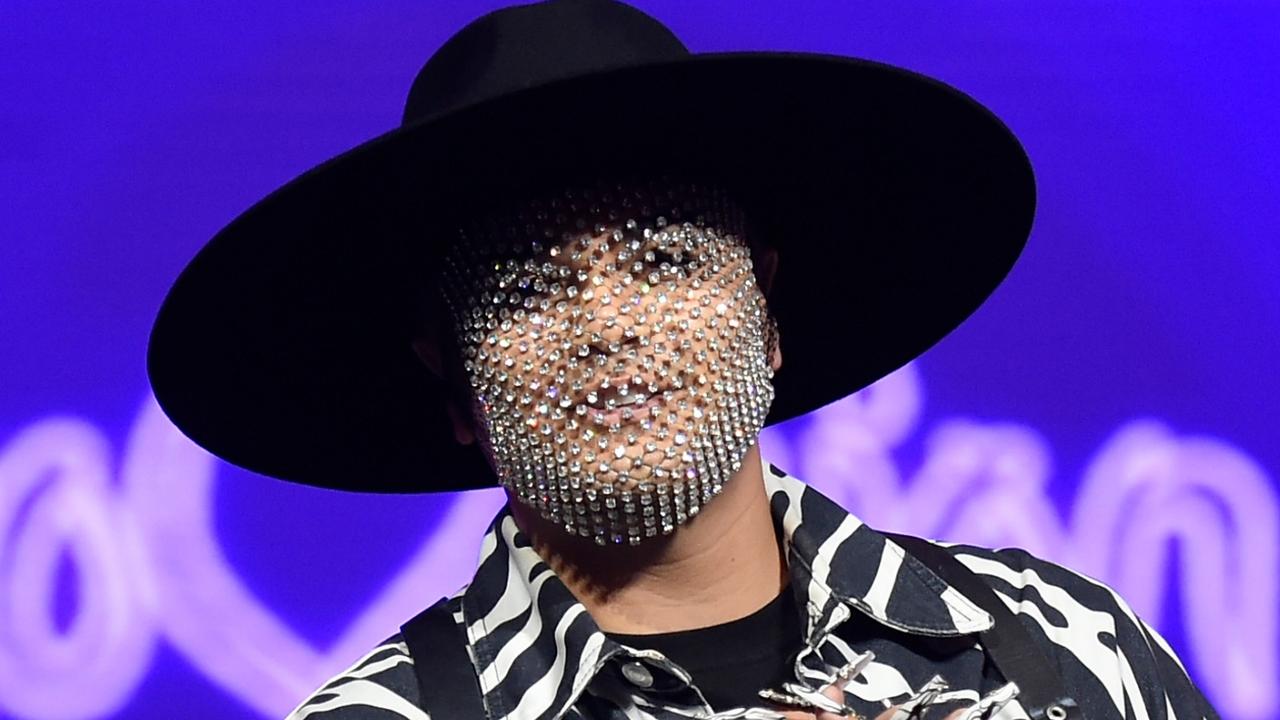

Euphoria is as much about the fraught nature of young adulthood as it is about the perils of addiction, and the series has combined these themes in Fezco, portrayed by social media trickster Angus Cloud. One of the breakout characters of the second season, Fezco is a spin on a particular Dylan McKay/Ryan Atwood/Angel archetype. He hasn’t always made the right choices, but he’s trying to now. As a viewer, to like Fezco isn’t to explicitly approve of the fact that he deals drugs, including to teens only a few years younger than he is; this isn’t a Walter White situation, in which rooting for the protagonist was a misunderstanding of how the series was presenting his megalomania and greed. But if the entire point of Euphoria is to probe at the limits of our empathy for characters whose actions are more often gray than black or white, then Fezco is more of a D’Angelo Barksdale or a Bodie Broadus than the Greek. Can you make bad choices and do bad things, but be a good person? What is the balance, and what tips the scales?

Trust is a tricky thing in Euphoria, since so many characters are either in a transformative period (Jules, Cassie, Kat) or caught in a cycle of self-deceit (Rue, Nate). The lies people tell and their far-reaching effects have been woven into Euphoria’s storytelling from the pilot; perhaps that’s why Fezco has emerged so appealing from these eight episodes — he’s the only person in the room willing to put the protection of other people over his own self-interest. Even in this finale episode, amid a turned-to-11 scene that feels like Levinson trying to outdo Scarface, Fezco’s primary concern is how to protect his younger brother Ash(tray) from the cops launching an all-out siege against their home. There goes those Little House on the Prairie-inspired dreams of growing old on a farm one day, surrounded by “horses, cows, pigs, chickens, goats … a little family,” and even the possibility of a proper first date with Lexi. Both now seem as improbable as Ash surviving that offscreen shot.

Fezco is a contrasting portrait of a young man who grew up too fast: his gentle speaking voice belies a rugged, feral physicality; his direct gaze can switch from curious to furious in a second’s time. Euphoria is often in conversation with or evocative of an array of other pop culture offerings, and if the antics at Euphoria High are Levinson’s version of Harmony Korine’s Kids, then everything involving Fezco is his spin on Nicolas Winding Refn’s Pusher trilogy. In the Euphoria pilot, when so many others reacted to Rue’s return to town after a three-week stint in rehab with shock, her dealer Fezco only expressed a sort of resigned worry. “Ain’t that the point?” he asked when Rue scoffed at the idea of staying sober. At Nate’s party that night, there was no hesitation when he confessed to her, “I like you, and I missed you, bruh. I’ve seen a lot of people die. None like you … This drug shit, it’s not the answer.”

Cloud makes clear the discomfort Fez carries. His line deliveries are measured, deliberate, with a little bit of a drawl; he holds eye contact even as his body language reads relaxed and unassuming. He doesn’t quite exude menace, but he radiates a kind of preparedness: a coiled spring full of energy yearning for release. Part of Fezco’s appeal is that he’s an enigma, from his last name to his age (20-ish, if we can believe Nate) to whether he dropped out of high school or college. What stands out in lieu of biographical details are his actions: bathing and caring for his grandmother; picking a high Faye off the floor; trying to protect Rue — “my family” — every chance he gets; gently wooing Lexi through lengthy phone conversations, quiet movie dates, and a shared affection for Bob Ross.

Unlike Nate’s poor-little-rich-boy characterization, Fezco hasn’t been over-explained to tedium, and he’s more humanized than the series’ higher-level drug dealers, Mouse and Laurie. Nate, Mouse, and Laurie all see Rue as damaged goods, and consider how to spin what they see as her weakness to their advantage. Fezco, aware that his own actions helped make Rue the addict she is now, carries that regret in their every interaction. It’s why he nearly pulls a gun on Mouse after he gives Rue fentanyl in “Stuntin’ Like My Daddy”; it’s why he refuses to sell to Rue in “Made You Look”; it’s why he agrees to intimidate Nate on Rue’s behalf in “The Trials and Tribulations of Trying to Pee While Depressed”; it’s why he beats in Nate’s face in season two premiere “Trying to Get to Heaven Before They Close the Door.” This mentality makes sense once Euphoria provides Fezco’s backstory in that same episode, explaining how he learned the dealing business from his “motherfuckin’ G” grandmother, Marie O’Neill, whose own use of violence had unintended consequences. And it also makes sense, somewhat, in “All My Life, My Heart Has Yearned for a Thing I Cannot Name,” when Fezco realizes from Faye’s tipoff that Custer is working with police, tries to stop Ash from killing him, then attempts to protect Ash by pretending he committed the murder. The close-up of Fezco’s fingers closing around the handle of Ash’s bloody knife is the most affecting shot of this episode, and a moment that seems quietly, irreversibly fated.

Then the shootout happens. The whacking impact of the rounds from Ash’s automatic rifle, Fezco’s insistent shouts to both Ash to give himself up and to the cops to stop firing at a child, and the red laser lights from the SWAT team’s guns cut through the haze of gunpowder smoke and destroyed drywall. This is Euphoria trying to be real life after playing with performative memory in Lexi’s Our Life play, but the series’ internal logic is so inconsistent that this scene doesn’t quite land outside of Cloud and Javon “Wanna” Walton’s committed performances. Was Custer on some kind of live call with the cops, or just recording what he hoped would turn into Fezco’s confession? This is the same police force whose members gave up chasing Rue just a few weeks ago? The same cops who, if they were investigating Mouse’s murder, should’ve known he was connected to other Big Bad Laurie, as Faye was trying to say while protecting Fez and turning on Custer? Was the SWAT team’s onslaught of violence against Ash (who is a child and from whom the police have no physical evidence) compared with the politeness with which the police arrest the wealthy Cal (whom they have on video committing myriad sex crimes) a purposeful point about classist discrepancies in law and order? Maybe?

Moreso, though, it felt like Euphoria choosing to sacrifice Fezco, who embodies so many of the series’ central questions about humanity, for the sake of a big, tonally out-of-place action showpiece. Selfishly, this is irritating given that catfisher and abuser Nate gets a redemption arc by turning in Cal, and Laurie and her locked door remain unscathed. But structurally, it’s bizarre that after spending so much time this season setting up the Lexi and Fezco flirtation, and after presenting Rue as making amends with people she’s wronged, Euphoria doesn’t have either of them mention what happened to Fezco. That arrest would certainly have made news. Wouldn’t Lexi, Rue, or hell, even Nate — Fezco’s long-running nemesis — have a reaction worth sharing with us? Perhaps Euphoria’s third season, ordered by HBO earlier this month, will mimic the second season in again starting off with a Fezco-inspired sequence. But that last shot of his shoe stepping on his bloodied note to Lexi as police haul him out of his home felt like a too-pat embodiment of “Art should be dangerous,” the line Levinson gave Our Life stage manager Bobbi. In seemingly shuffling off the stage one of its most compelling and complicated characters, Euphoria didn’t need to be so literal.

https://news.google.com/__i/rss/rd/articles/CBMiS2h0dHBzOi8vd3d3LnZ1bHR1cmUuY29tL2FydGljbGUvd2hhdC1oYXBwZW5lZC10by1mZXpjby1ldXBob3JpYS1maW5hbGUuaHRtbNIBAA?oc=5

2022-02-28 07:04:53Z

1317933862